The two Ronnies

As snooker's greatest, most charismatic player, Ronnie O'Sullivan has much to enjoy in life. Why then has he turned to Prozac and the Priory to lift the depression that can envelop him? Well, for a start there's the fact that his dad is serving a life sentence for murder...

Gordon Burn

Sunday December 2, 2001

Observer Sport Monthly

www.guardian.co.uk

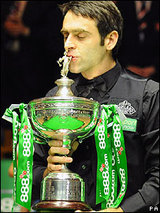

In the days after Ronnie O'Sullivan finally did what everybody had been telling him he was going to do for nearly as long as he could remember and won the world championship in May this year, a haunting detail emerged about how his father had been kept up to date with what was happening, in his cell in a prison on the Isle of Sheppey, in Kent. It was night; the period of free association was over and the prisoners were sealed off in their separate cells. 'Big Ronnie' as he is known, although he is physically smaller than his son, either couldn't or didn't want to hear what was happening between Little Ronnie and John Higgins in Sheffield at first-hand and so arranged to have it passed on to him in coded form from somebody else on his landing: a click of the fingers meant Ronnie was at the table; a kick against the door meant that Higgins was taking a shot; all the Banshee yells and mug-banging when it was over meant that Ronnie, leading 14-8 after a hot burst in the afternoon session, had run out the 18-14 winner and in the process pocketed a cheque for £250,000. No problem. Nothing is a problem. Lovely.

It's a scenario that plunges you back into the time of scratchy movies where the cons wore pyjama suits with black arrows on them and Cagney was king; back to the days of the early crime shows like The Naked City and Dragnet.

It's certainly a world away from the Sheffield Crucible and all that snooker has become: corporate jolly-ups and subliminal brand identification and, in the immortal words of Barry Hearn, 'all that patronising bullshit'. Throughout the Eighties, Hearn's Matchroom headquarters in Romford, Essex, was bullshit central, with Barry giving GBH of the earhole to anybody who cared to push his button and get him started on aspirational this, and socially hygienic that, and how everybody associated with the Matchroom set-up stood to make fortunes. 'At the end of the day, the only things we wanna see is the numbers,' the Bazza used to like to say. 'We're all in a numbers world. "Tell me what the ratings were." That's the only reaction.'

Ronnie senior listening to Ronnie junior progressing towards his first world title via a series of knocks and taps on the woodwork and the prison plumbing carries a heavy echo of the Fifties London of the gang wars between family 'firms' like the Richardsons and the Lambrianous, the Maltese Messina brothers and the Krays, when Ronnie and Reggie's billiard hall, The Regal in Eric Street, was the haunt of every up-and-coming thief, fence and racketeer in the East End.

And it turns out to be not just an imaginative link but a real one. Ronnie O'Sullivan's grandfather, Mickey, was a boxer. And so were Mickey's brothers, Danny and Dickie (ring name, 'The Toy Bulldog'). They knew some renown in post-war boxing circles. They were 'The Fighting O'Sullivans'.

Danny was British bantamweight champion 1949-51. The brothers merit a mention in a memoir by Charlie Kray, in a chapter devoted to Ronnie and Reggie's early boxing exploits at the famous Fitzroy Lynn Club, whose members at the time, in addition to the O'Sullivan boys, included Freddie King, later to be Barry Hearn's business partner in his East End fruit machine and amusement arcade 'empire'.

It's a legacy that Mickey's grandson, Ronnie, wears like a raiment - sackcloth shot through with threads of gold; not boastfully, but not meekly either. Something that the sociologists call 'deviance disavowal' was central to how Barry Hearn proceeded in the marketing of 'sports-leisure': it explains why his players were always booted and suited and immaculately prime-time; it explains why Tony Meo was instructed never to associate publicly with his old partner-in-crime Jimmy White while he was with Matchroom. 'The sadness is that we need the Higginses and the Whites, these flamboyant, natural players, we need them to keep the game fresh and alive and exciting,' Hearn once told me. 'But from a commercial point of view, nobody needs them at all. No multinational would touch them. Which means they can only ever get their incomes from tournaments and live-show exhibitions, which is a dwindling market.'

Although he was with Matchroom for his first six years as a professional player, Ronnie O'Sullivan's outlook, in keeping with his innate sense of street 'suss', has consistently been more realistic. It's all on the record; it's archived in big black headlines: his father stabbed a man to death in a nightclub brawl and was given a sentence of 18 years. In the place that Ronnie comes from such things happen. Stuff happens. Such is life. 'I got nothing to hide,' is what Ronnie has always said, and it's what he repeats to me now. 'They can come and look at me all day long and they'd get nothing. I've got a nice family, an' I'm happy to see that, an' if people wanna be associated with us, it's up to them. I'm not going to lose any sleep over it.'

Ronnie believes in family. It's the bedrock of his life. He believes in what, in his book, Charlie Kray calls 'that greatest of all "inner laws" - family love'. And the top and bottom if it, the alpha and omega, is his dad. Ronnie loves his dad. He loves to talk about him, as if this talking might, in a funny way, give him another lighter life separate from his banged-up boring prison existence.

I'd written about Ronnie once before, many years ago when he was just starting and everybody was tipping him to be the youngest ever world champion at 17 or 18. (He had made his first century at the age of 10 and his first competitive 147 when he was 15.) On that occasion, I'd had dinner with Maria, Ronnie's mum, in a West End restaurant, and Ronnie reminded me of a detail in the story I'd forgotten: 'You met a man in Langan's when you were eating with my mum. He said what a great guy my dad was. He told you how much he liked my dad.' A condition of the interview with Ronnie this time was that his father would be a no-go area; strictly off-limits. But it was never on the cards. He can't not talk about him, and he tends to get noticeably more 'outward' and charged up when he does. I told Ronnie I imagined his dad looking like Ray Winstone, like a lot of the men eating in Langan's Brasserie had that night. I'd never seen a picture, but that general type. 'Yeah', Ronnie said. 'I dunno. He's a cross between Del Boy, Joe Pesci and Ray Winstone. An' then he had the sort of charisma of Al Pacino. He had a lot of style, and a lot of class. He could put on a bin-liner and look good, y'know. He's one of them people. He's quite lucky like that.'

Ronnie, as he himself would put it, gives the appearance of being pretty 'chilled'. ('Chillin' about' he offers as his favourite way of passing the time. Which means? 'Getting up in the morning, maybe do an interview or some'ink, have a nice lunch, do a bit of shopping, pop in an' see my mum, see what she's up to, make a few phone calls, make sure my properties are being looked after all right.') At the beginning of this season the tournament dress code was relaxed by the sport's governing body, World Snooker. Some players have taken it as the cue to large it, with pegged and draped trousers, full-roll collars and duotoned patent-leather pimptastic shoes. Ronnie, though, has gone on turning out in the same shined-up bible black and extra-long sleeve, £27.50 drip-dry M&S shirt. 'When Armani, Gucci, Prada start sending me stuff an' paying me to wear it,' he said, 'then I'll wear that gear. For the minute, though, I'll stick to this.' Away from the table he has the off-hand, wised-up attitude to his appearance of the typical Chingford-Chigwell, Epping Forest-borders 'face'; nothing flash; nothing too 'pie-and-mash'.

Ronnie was 16 when his father was sent away. It was his father who had got him going on the snooker when he built a snooker room at the end of the garden for Ronnie when he was about seven. Ronnie's early years were spent on the notorious (notoriously grim) Holly Street estate in Dalston, close to his father's old stomping ground in Hackney. Ronnie senior worked as a steward on the railway. He had married Maria Catallana, the daughter of ice-cream-making Italians, and they had moved into a high-rise in the East End, which was all they could afford. 'They met at a Butlins holiday camp,' Ronnie said. 'My dad was a chef and me mum was a chalet maid. I think me dad was a chef, anyway; or he was just having a laugh. Whatever he was doing, he was just doing what I suppose a lot of 17- and 18-year-olds do - just trying to get out in the world and enjoy a bit of it. And that's fate really, how you meet. Especially the time they've been through.'

They lived in Ilford through most of Ronnie's school years and then, in the late Eighties, they were able to do what all real East Enders do, which is move up into arborial Essex. At the time of his conviction, Big Ronnie was being described in the papers as a 'porn baron'. Was he? 'Dunno. If you want to call it that', Ronnie said. 'It was more like a bookshop. It was more like a bookshop with an adults section in there where you could buy stuff.'

Where was it? 'Well he had a few in Soho, and he had a few around the outskirts of London. But I was so young at the time I wasn't really interested, to be honest with you. As long as I had me tenner for me taxi down the snooker club and me food money, I weren't really bothered. And that was about as far as it goes.'

Maria was involved with it as well? 'Nah, my mum didn't have a clue about any of it at all. She was just, like, a brilliant cook, brilliant mum, brilliant wife. My mum and dad were like an item, so she was just there with my dad. So she don't know nothing about the business.' I thought she took it over when he went inside? 'All she does is collect the rents and that's it, really. As soon as me dad went away, it was too much for me mum to really do. So the people that were in there working, they just took over the responsibility, and made sure the rent was paid.'

Ronnie claims that he rarely missed school (although this seems to be contradicted by a number of tales he will tell against himself later). But every second he wasn't in school he was in snooker clubs in Barking and Ilford. 'Breaks' in Ilford, where he has suggested we meet, still has echoing stone stairs and a rickety cage lift and was probably once like Zan's in Tooting, as described by Jimmy White in his autobiography: 'It looked warm and inviting, dark and mysterious as a cave... The floor was awash with cigarette ash and stubs and there was a kind of dusty, musty, beery, smoky, almost soot-like smell... If, like Alice, I had fallen down a rabbit hole and dropped into Wonderland, it would have been like this.'

'Breaks' in Ilford these days is more... 'More Indian-restaurant looking', Ronnie says, clocking the swansneck lamps and the burgundy flock-wallpaper. It's a place he knows well, having spent more time in it than probably any other place anywhere. His feelings about 'Breaks' are not entirely swamped in sentiment. When he was there, he was there to work. Which didn't mean playing cards, didn't mean playing the fruit machines; it meant hour after hour, six hours a day, of practicing snooker. His father cracked the whip. 'To be honest with you,' Ronnie said, getting a fag on, 'I don't like snooker clubs. I don't. I go in there to do what I've got to do because I have to go to tournaments and play. I enjoy the tournament side of it, but I don't enjoy practising. It does my head in. Drives me mad.

'When I was a younger kid I was inbred with, y'know, get up, go for a run, get down the club at eight in the morning, bottle up, and get on the table. Because I wanted to feel I was putting my part in. Whenever I had a bit of time and I could help brush tables, I did it. Whenever the gels behind the bar needed helping out, I'd do it. So I have worked all my life. Instead of starting my hard work at 17, I started at eight or nine. I neglected going to youth clubs, going to football, going to discos at 11 and 12. So I started work a lot earlier than most people start. I started my career when I was eight. So, y'know, I've had a long time in snooker. And for me, at the moment, practice isn't what it's all about. I ain't playing til Monday and I want to enjoy today. I want to sit down and relax with my girlfriend, she's going to cook me a nice dinner later, an' I don't wanna fucking hag her with my frustrations that I get with this game sometimes. I feel I put myself through enough shit over the years and I feel I don't want to do it to myself at the moment. An extra hour on that table's not going to make me play any better Monday. That's something I've had to find a balance with, and I think I've found it.'

He was having a week off between tournaments. Four days earlier he had crashed out of the British Open in Newcastle, losing 6-4 in the semi-final to a relative unknown, Graeme Dott of Scotland. After making five centuries in the previous 20 frames, he had suddenly turned into what he had been encouraged to think of as 'the old Ronnie' : he was loose and listless and conceded two frames with enough balls left on the table to win them. At the press conference afterwards he had been close to tears. 'I played brilliantly in my first three matches,' he says, 'and then it just totally went out the window. It was the worst performance I've ever done in my life. It was fucking pathetic. Really pathetic. I was 4-3 up and couldn't wait to get out of the arena because I was disgusted with myself.

'When you're buzzing and you're playing well, you don't think about anything; you just get down and pot balls. But when you start struggling, you start to think about why you're struggling and sometimes you can drive yourself mad. I've done that in the past and it can be quite damaging on the brain; it's hard to get rid of those negative thoughts, and start to reprogramme your brain all over again. But you live with that head, and things stick in that head. It's hard to erase them. I'm fucking crazy sometimes.'

Clive Everton, the editor of Snooker Scene and television commentator, has suffered from clinical depression. And he says he has recognised the symptoms in Ronnie. 'You can see it come down. At his best, he is the best player who has ever played the game. He's beyond excellence. But there are two Ronnies: one's an authentic genius comparable in his field to Best or Beckham; the other's a depressive whose great talent can be a burden and the game an ordeal. You can see it happen: his mood changes from upbeat and positive to bleak and barren.'

At Everton's suggestion, Ronnie consulted Mike Brearley, the former England cricket captain, now practising as a psychoanalyst. At his dad's suggestion he booked an appointment with the TV hypnotist, Paul McKenna. He has tried Prozac and turned to the Samaritans. Last summer - 'I just got to a stage where I felt so depressed. Just depression. Serious depression. Anxiety attacks' - he checked himself into the Priory, and stayed there for a month. 'I didn't speak to anybody about it', Ronnie said. 'I didn't even ask my dad. I told my dad: I'm going, and that is final. I didn't really want visits. I was quite happy just to get on with it and get out of there, really. Do your time and get out, innit? That's what it was like, doing time.'

Ronnie's father started his life sentence in 1992. Three years later his mother served 12 months in prison for VAT fraud. Ronnie was 19 at the time and his sister, Danielle, was 12. Ronnie went on a 'bad wobble' then and says he must have been unrecognisable to his mother by the time she came home. When she did come home, she slung him out. 'Because I was too obese, too arrogant, too... embarrassing. Just a waste of space, and too time-consuming for her, really, and for everyone else around me. Big bed strapped to my back and wherever I went, I just slobbed out. I wouldn't even go out the house.'

Ronnie describes his mother as 'very shrewd. I mean, it's very hard to get in her circle. It's 50 times harder to get in her circle than it is in mine. Don't even go there. It's one of them.' But in many ways it seems that the wrecked Ronnie he showed her when she came out of prison is the Ronnie he had been trying to get her to see for a very long time. 'Mum used to say, "Oh so and so's bad for ya... he's bad forya"', Ronnie says. 'But she didn't know half the truth. I was the one that was bad. All my life. I used to lead everyone astray. An' I've never told my mum that. I've been a great manipulator, getting people to do things. Even when I was at school, the two best runners for the cross-country, I got 'em in a taxi an' said, "C'mon we're going out. We're gettin' outta this". Cause they didn't want to do it. I ordered the taxi, got it to come to the school, we was all hidin' underneath the seats. But I've always been the one for goin' like "Where we goin' tonight?" Credit card in the back pocket an' let's go. Three or four days, hotel room booked... My mum would blame them, but they was quite happy just to come home at one o'clock in the morning. It was me that was like "No, we gotta go on somewhere else now. It's all sorted. No worries". I thought it was all these people that were around me and made it all excitin' and that it was their fault. But it wasn't their fault. It was all me.'

The following Monday, Ronnie played his first-round match in the LG Cup at the Guild Hall in Preston. He won 5-0. On Wednesday, he would put together a virtually flawless maximum break in just six minutes, 19 seconds. But Tuesday morning found him slumped in the lounge at the Holiday Inn looking dog rough. He said he'd kept the television on all night and had hardly slept and then had woken up in the frame of mind where he didn't think he was capable of ever winning another tournament. Plus a newspaper the previous morning, giving a roll-call of the usual 'bad boy' players, had ended up with a reference to 'mad Rocket Ronnie O'Sullivan'. 'It annoys me sometimes,' he said, 'd'you know what I mean? Cause I'm not "mad". I'm quite a normal person who does normal things. The only thing that is bad in my life at the moment is probably that I smoke cigarettes, and I really don't like doing that even. So, take that away, I'm quite normal. But, y'know, people got this perception of me that I'm some sort of... nutter. Like a time-bomb waiting to go off. Obviously based on my past: head-butting officials [he was fined £20,000 for head-butting a press officer at the World Championship in 1996], smoking a bit of pot [he forfeited his title and the £61,000 first prize after testing positive for cannabis at the 1998 Benson and Hedges Masters]. Although it is quite an unstable thing really, I suppose, if you look at it that way. That's why I don't want to put myself on the edge, or gamble my career down the drain. I don't enjoy that sort of life. There's no need. It's tough enough as it is. I want to stay on the straight and narrow road.'

Ronnie was on his own in Preston apart from a 73-year-old coach called Frank Adamson who he regards as a calming influence. 'We do our bit of practice, he eats his fish'n'chips, I do my little thing, and there's no, like, pressure.' He gets jumpy when there's too many people rippling around him. He doesn't have many friends. 'I don't want many friends, anyway. I'm happy just the way it's going, and that's it really. I don't want too many people in my life. I get drained'.

He's been shedding people. In April this year he parted company with his manager of several years, Ian Doyle. Since the beginning of the season he has been travelling without his 'mind guru', a 6-foot-10-inch fish farmer from Lincolnshire called Del Hill. When he'd get panicked at the thought of making the winner's speech at a sponsors' dinner, it was Del who would sort him out. When he was in despair during the interval of a match and feeling in need of a cuddle, it was Del who would provide it. But at the end of the day there's only ever going to be one main man for Ronnie: his dad. He has his phone card where he is in prison, and they talk on the phone all the time.

'I love visiting him, I love seeing him, I love talking to him, sometimes. Not all the time. We drive each other mad. He's always buzzing and positive, positive. Big positive vibe. An' sometimes I just can't be bothered to listen to it, an' I'm just like... I just feel like saying, "Dad, I wanna just relax on the settee". But obviously I can't say, "Oh just bugger off and leave me alone". Sometimes I do. Sometimes I say to him, "Dad, just drop me out, I'm havin' a bit of a bad day. Phone me tomorra". An' he goes, "Awright then. Love you lots". An' we blow kisses down the phone to each other. And then he rings me up the next day an' I say, "Go on, start. What you got to say to me today?" An' we just talk.'

When he was asked once who his heroes were, Ronnie came up with the following: Tiger Woods, Michael Schumacher, Andre Agassi, Pete Sampras, John McEnroe, Howard Hughes. Spot the odd man out. On the other hand, the choice of the billionnaire recluse who became the supreme American symbol of what it means to be a free agent and live by your own rules, makes some kind of sense. Like Howard Hughes, Ronnie short-circuits rationality and appeals to the deep places of the imagination. Among footballers, we officially admire Sir Geoff Hurst and Sir Bobby Charlton, the ambassadors of the game. In snooker, the official recipients of our admiration are Ray Reardon and Steve Davis, John Parrot and Stephen Hendry. There has always been that divergence between our official and our unofficial heroes. It is impossible to think of Ronnie, as Joan Didion once wrote of Hughes, without seeing the apparently bottomless gulf between what we say we want and what we do want, between what we officially admire and secretly invest in.

As we sat at the Holiday Inn's first-floor window, David Beckham's face, advertising sunglasses, kept gliding by on the side of Preston's double-deckers. 'I know David,' Ronnie said during a lull in the conversation, 'he's from where my bagel bar is, Chingford. He is is a proper, proper nice person, the sort of person that if your daughter come 'ome with 'im, even if he wasn't a superstar, you'd go 'Ahhhh. You've hit the jackpot.' I haven't seen him since he started going out with Posh. But I'm sure we'll meet up along the way.' Would you invite Hello! into your lovely home? 'Naah. Well, you never say no to nothing. But naah. Fifty grand to let someone into your 'ouse? They've offered before an' we won't have it. I wouldn't have my wedding in either. I wouldn't have anyone at my wedding. Nobody. I'd have a witness, 'cause you got to have one of them. But it would just be a quickie. "I loveya, okay now let's crack on." Because I can't be doing with all the big parties and all that rubbish. It bores me. I don't even like going to functions an' things like that. Awards bashes. Like I want to sit there and listen to everyone getting their tongue down each others' trousers. Get a life. Being the main person at a big function like that becomes like my worst nightmare come true.'

Taking the applause of the crowd makes him noticeably uneasy.

After making the 147 at Preston he beat a retreat and disappeared behind the door of the dressing-room, a room no bigger and no better-appointed than a cell, to where the sound of cheering and clapping pursued him. It was an afternoon session, and so Ronnie Snr. had probably been able to follow what was happening on the television.

'He's my guru,' Ronnie said, 'if you like. Someone that I confide in and I ask his advice. And he hasn't done me wrong so far. So, y'know, I think he's done pretty well for himself. I know he's ended up where he's ended up, but... So have a lot of people. That doesn't make them bad people. It's just being in the wrong place at the wrong time. It could happen to anybody.'

29. 4. Robert

Návštěvnost stránek

ANTEE s.r.o. - Tvorba webových stránek, Redakční systém IPO

![Welsh Open[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=3689245&width=160&height=174)

![Ronnie_OSullivan_Snooker_Champion_PTC7_2011[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=2439625&width=160&height=151)

![topimage[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=2498497&width=160&height=141)

![08%20pls%20ronnie%20trophy[3].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1189442&width=160&height=198)