Ronnie's profile written for Inside Pool Magazine

The Snooker Genius

Kevin Fontaine

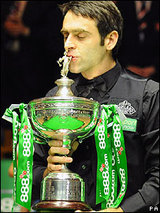

He appears to possess nothing special – you wouldn’t look twice. He is above-average handsome with jet black hair cut in a pseudo-Beatles style, marathoner lean with a pleasing angular face and sharp eyes. Yet in the parts of the world where snooker is the king of cue sports – he is a god – a man who could not walk down the street without recognition. Think Tiger Woods, think U2’s Bono, think Tom Cruise.

He’s Ronnie O’Sullivan – the man snooker historian Clive Everton called, “the most extraordinary natural talent the game has ever known.” A cue in his hands, it is said, is like a brush grasped by Picasso. His 5 minute and 20 second maximum 147 (a 147 is when each of 15 pocketed red balls is followed by a black ball and then the remaining 6 colored balls to total 147 points) during the 1997 World Snooker Championship is regarded as the single greatest feat in snooker history – the snooker equivalent to Roger Bannister’s sub 4-minute mile.

O’Sullivan was a child prodigy. Born in Birmingham, England in 1975, he was introduced to snooker at age 7. A wisp of a boy with tar black eyebrows standing in bold relief against his skin, extra pale from the gray weather of Southern England, the snooker cue towered over him. Yet, in his hands, even then, the cue expressed his genius. He won his first tournament at age 9 and scored his first century, 100 consecutive points, at age 10 – the youngest ever.

There was a dark side. Every stroke of the cue either fed or starved his self-worth. A performance that did not meet his utopian standard would stain the rest of the day with a molten anger that would erupt at the merest provocation.

He turned professional in 1992 at age 17. Nicknamed the “Essex Exocet” (an exocet is a small, French-built anti-ship missile) and “The Rocket” for his rapid-fire pace of play he almost immediately became a dominant force. Fueled by unrelenting emotional volatility and addictions to alcohol, food, and cannabis, in a short order O’Sullivan attacked a reporter, head-butted the son of a referee, urinated in public, crashed three BMW’s, and generally caused, or was associated with various forms of mayhem. The British Tabloids loved him. Each back page story of O’Sullivan’s exploits sold more papers and solidified his popularity and reputation as the impulsive, emotionally unstable, bad-boy genius of snooker.

O’Sullivan the snooker player stuns audiences, opponents, and commentators. For never has a player possessed, in such abundance, the talent required to bring the complicated game of snooker to its knees.

The cue ball behaves for O’Sullivan like it does for no other. His sense of pace, of how firmly to strike the cue ball, of how the cue ball will react based on the objects balls’ putting angle and where the tip strikes the cue ball is unparalleled. O’Sullivan’s genius lies in the way the cue ball obeys his every whim – as if he has it under hypnotic power.

The sheer physical talent stems from the coordination of eye, brain, and body. There is no distortion – the eyes perceive, the brain processes, the body performs. He just looks, sites, and strokes. He is unencumbered. The auto-pilot of his genius carries him.

What the observer sees is kinetic poetry. O’Sullivan moves smoothly around the table, rarely lingering. The pace and assuredness of his play suggests that he has already plotted the shooting sequence of the entire table in his mind. His cueing – the way he strokes the ball – the set-up, the lithe posture, the take back, the eye lock, the ever so brief pause, the forward stroke, the follow-through and the pause-hold are as simple as they are elegant. The grace is confirmed by the sound the tip of the cue makes when it strikes the cue ball. The sound is distinctive and melodic: a sound no other player can produce – a crisp, ringing click – virtually a musical note. You could close your eyes and hear the music; the virtuoso performance as O’Sullivan makes the balls disappear from the surface of the 12 by 6 foot table.

Despite many tournament wins, the precocious talent of O’Sullivan has produced only two World Snooker Championships, the measuring stick upon which snooker greatness is assessed. Genius is a rigorous task master that makes formidable demands on the soul. John McEnroe never won another Wimbledon or any major tennis tournament after the age of 24. Bob Dylan’s best songwriting came when in his 20s. Their genius never fully realized – never taken to the level commensurate with expectations the talent warranted. Will O’Sullivan, now 30, when all is said and done, also be considered an underachiever – a genius never able to fully exploit his gift?

Written for Inside Pool Magazine

Kevin Fontaine

In the self-contained world of the Venetian Resort Hotel Casino in Las Vegas, Nevada he is as anonymous as anyone. He is handsome, dark hair, marathoner lean with a pleasing angular face and slightly sad eyes but he will not stick out in the flurry of tourists, honeymooners and gamblers who perpetually invade this strip of desert. On the surface he appears to possess nothing special – you wouldn’t look twice at him. Yet in the parts of the world where snooker is the king of the cue sports – he is virtually a god – a man who could not walk down the street without being recognized. Think Tiger Woods, think U2’s Bono, think Tom Cruise. The lights and activity and crowds of Las Vegas, it seems, are a furlough for him – a furlough from the fame and notoriety and from the personal struggles that have, at times, overwhelmed him.

- ---------------

Despite the family disintegration, despite the depression and its co-pilots - the intractable anger and the paralyzing anxiety, despite the various addictions O’Sullivan, the snooker player generally leaves crowds, opponents and commentators awestruck. For never has a player possessed, in such abundance, the range of talents and skills required to bring this complicated game to its knees.

In the words of former World Champion and BBC commentator John Parrott after witnessing O’Sullivan score a seemingly effortless 137 in the 2006 Masters Tournament in London, “Do you know this is actually a hard game? You would never know it from that – I mean that is as good – anyone who has ever played this game and picked up a cue are pulling for this boy because that is the best anybody can possibly play. . . When his attitude is right and he’s playing like this he is unplayable.”

What makes O’Sullivan so special? What underlies his snooker genius?

First, and foremost O’Sullivan possesses a snooker brain – the capacity to see and project in the mind the seemingly endless options and possibilities available in a frame of snooker. Seeing the subtleties in the balls – the clusters and how too gently nudge a ball into a position where it can be pocketed – how to free the black spot so that once the black is pocketed it returns, unimpeded, to its rightful position on the table so it can be, repeatedly, deposited into a corner pocket.

The brain is also the epicenter of defensive play – of safeties. O’Sullivan is one of the best at looking for a path in the complex array of balls so that your stroke shaves a ball and propels the cue ball away from offensive possibilities – ideally behind another ball that cannot be legally struck – producing the games namesake - a snooker.

Then you have what everyone pays to see - O’Sullivan’s breathtaking offense. At the business end of the table, among the reds and the black, his ability to quickly ring up a massive frame winning score is unparalleled. The cue ball behaves for O’Sullivan like it does for no other player. His sense of pace, of how firmly to strike the cue ball, of how the cue ball will react based on the putting angle and where the tip strikes the cue ball is poetic. The mystery of O’Sullivan’s genius lies in the way the cue ball obeys his every whim – it’s as if he has the white sphere under some sort of hypnotic power.

The physical talent, the ability to pocket shots that most elite players wouldn’t even attempt must stem from interplay of eye, brain, and hands. In short, there is no distortion – the message travels with perfect clarity – the eyes perceive, the brain processes and the body performs. Harmony and synchronicity between these systems allows O’Sullivan a degree of eye-hand coordination that has rarely, if ever, been seen around a snooker table. Indeed, when he is in optimal form the difficulty of a given shot is irrelevant - easy shots hard shots – O’Sullivan doesn’t need to distinguish them. He just looks, sites, and strokes. He is unencumbered. His genius takes over – perfection is the result.

If this weren’t enough, another skill that separates O’Sullivan from the pack is that he is ambidextrous – performing with near equal facility playing left handed as he does right handed. As such, he virtually never needs to use the mechanical bridge (or “rest” as it is called in snooker-speak) – the device you rest your cue stick on when you cannot comfortably reach the cue ball. Playing on 12 by 6 foot tables the occasion to use the bridge arises often, however, O’Sullivan’s ability to play opposite hand gives him a massive advantage because it is much tougher to leave the cue ball where you want for your next shot when using the bridge.

It is fairly common, when O’Sullivan is flying through a frame, to see him alternating between right to left-handed play without good reason, other than one assumes, to minimize the disinterest that afflicts him when he knows he cannot miss.

O’Sullivan’s talents coalesce to produce what appeals most to the masses, his capacity to make the game look so simple, so pedestrian. Watching O’Sullivan in full flight gives you the delusion that you could pick up a cue and imitate the performance. Clearly a delusion because a lifetime of playing and watching snooker would not bless you with what it takes to do what O’Sullivan can do, seemingly so effortlessly, on a snooker table.

O’Sullivan has over 440 competitive centuries and counting.

- ---------------

O’Sullivan’s third round loss in the North American Open was not met with despair; indeed, strangely, he was happy. Apart from the vague emptiness that came from separation from his girlfriend and their 5-month old daughter he was animated, even energized. The game of 8-ball, his struggles with the break aside, came easy to him, certainly easier than he had expected. Even with only a weeks preparation before competing he wasn’t outclassed by the best pool players on the planet and, perhaps most importantly, he did not see anything occur on the tables at the Venetian that made him think he couldn’t beat these players.

This realization, it seems, enthused him. As he told British newspaper columnist John Duncan, “I've got that old fire back, that I could feel the warrior back in me. It's what I miss. Two days ago I thought it would take me two years to conquer this sport. Now I think I can do it in six months.”

It is not the obscene, for cue sports anyway, money on offer from the IPT that will motivate him to work to master 8-ball – no, wise investments of his snooker and endorsement earnings mean that he could never strike a cue ball again and live comfortably over a few lifetimes – it’s the thrill of competition, the passion, and the sense of danger, the buzz, the charge he gets as an entertainer, that has produced this pseudo-mania. He knows he’s not the best 8-ball player – he will actually have to work at this so - he has cause again.

So, leaving Las Vegas O’Sullivan was emboldened – confident that he could, with work on his break, play the game of 8-ball with the same vigor, flair, and effectiveness that he has long enjoyed in snooker. The challenge to make his genius fully translate to a new cue sport left O’Sullivan buoyant.

- ----------------------

Two weeks after the IPT North American Open O’Sullivan competed in the Northern Ireland Trophy, the first of seven major events on a dwindling snooker calendar. (The loss of tobacco sponsorship after the 2005 World Championships has left a financial void in snooker that has yet, and might never, be filled) If anyone expected a diminished performance from O’Sullivan’s having recently played on the smaller pool tables, it was dispelled quickly. After scratchy play in the first two rounds, he found his touch and played flawlessly, as good as ever. In particular his best-of-eleven frame semi-final match against Welshman Dominic Dale was one of his finest performances in recent memory. He whitewashed Dale 6-0 in a match that lasted under an hour. O’Sullivan had 8 breaks over 60 and outscored his opponent 608 to 29 in what can only be described as a massacre.

To the observant eye you could see remnants of his recent 8-ball play. Once a frame was secured, O’Sullivan would employ looped or closed bridges as he stroked the cue ball. Virtually never seen on a snooker table these so-called American-Style bridges suggest that O’Sullivan was working on his pool game while competing at the highest level in snooker.

Although O’Sullivan lost 9-6 in the final to 19 year-old Chinese sensation Ding Junhui, he was happy with his play, “I enjoyed the tournament. I came here to play attacking snooker and enjoy it. That was my aim and I’ve achieved it.”

- ---------------------------

After about a week of practice to introduce himself to the intricacies of 8-ball, Ronnie made his IPT debut at the Venetian in the North American Open. In the four race-to-eight matches of the first round he won two matches and lost two but with three of five players in the group advancing, he advanced to the second round.

In round two O'Sullivan won two of his five matches, advancing only because of a higher games-won percentage (thanks mainly to a hill-hill 8-7 loss to Mika Immonen).

Ronnie was eliminated in the third round after losing three of four matches.

Despite the 58th place finish, paying him $10,000, there was reason for optimism. O’Sullivan, who won 50% of the racks he played, lost a number of close matches, including an 8-6 loss to Francisco Bustamante and hill-hill losses to the aforementioned Immonen and Corey Deuel, three of the world’s premier pool players.

O’Sullivan’s strength, pocketing balls, was clear, as was his quick-fire, exciting style of play. He sites and picks his patterns quickly, without indecision. As such, it was not uncommon for him to run the seven object balls along with the eight in less than 90 seconds, “a breathtaking pace” according to one commentator.

His ball pocketing prowess and swashbuckling approach to sinking the spread of balls was recognized by Pilipino pool wizard Bustamante, “I was so nervous – I told him. He is a great player. He is number one in snooker. So playing pool I know he’s going to putt every ball. So that’s why if I don’t break, don’t make a ball I’ve got no chance against him because he putts the ball. He’s very good.”

To be continued....

29. 4. Robert

Návštěvnost stránek

ANTEE s.r.o. - Tvorba webových stránek, Redakční systém IPO

![Welsh Open[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=3689245&width=160&height=174)

![Ronnie_OSullivan_Snooker_Champion_PTC7_2011[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=2439625&width=160&height=151)

![topimage[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=2498497&width=160&height=141)

![08%20pls%20ronnie%20trophy[3].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1189442&width=160&height=198)