The 2000s - first decade

CHINA IN THEIR HANDS

The first world ranking staged in China was in 1990. The second was in 1999.

But in the 2000s, China’s place as a central powerbase for snooker was cemented, largely due to the exploits of one of its own sons.

Ding Junhui was invited to the 2002 China Open in Shanghai as a 14 year-old wildcard. He had been identified as a promising up-and-comer in the Chinese junior ranks and took two frames off Mark Selby.

Peter Ebdon described him as “the finest 15 year-old I have ever seen” and a huge amount of hype began to swirl around him.

It increased when, in 2002, he won the Asian under 21 title, the Asian amateur title and then the IBSF world amateur title.

In 2003, he was given a wildcard to compete on the main tour. Talk about a culture shock, from China he came to play full time in the UK where, like so many, he found the qualifiers tough.

Inevitably the knives were almost immediately out for him but Ding put up a good showing when, at 16, he became the youngest player ever to compete in the Wembley Masters, beating Joe Perry before losing in a decider to Stephen Lee.

Due to financial problems afflicting the sport, the China Open was not staged for three years until returning in 2005 on a one year deal.

Ding was excused having to qualify and selected instead as a wildcard so that his home fans could see him up close.

His performance in the event was sensational. He turned 18 that week but played like an experienced old hand, not a relative rookie.

Ding defeated Marco Fu, Peter Ebdon and Ken Doherty to reach the final and then, in front of an estimated viewing audience of 110 million in China, beat Stephen Hendry 9-5 to win the title.

Because he was a wildcard he did not, officially at least, bank any prize money and actually went down in the rankings.

But Ding’s victory was worth plenty to snooker. It lit the blue touch paper for a bona fide boom that has seen millions of Chinese take to the green baize.

When people ask me what the best event I’ve ever attended is, I would name this 2005 China Open.

It was wonderful to see the reaction of the home crowd to Ding’s success and there was a feeling, justified as it has transpired, that it would be very important to the future of snooker.

There are now two ranking tournaments in China, both financially underwritten by the Chinese.

Players are treated like Hollywood film stars, walking the red carpet on tournament launch days and pursued relentlessly by autograph and photograph hunters.

More tournaments will surely follow, particularly as Chinese players improve.

Liu Song reached the 2007 Grand Prix quarter-finals, Liu Chuang qualified for the Crucible in 2008 and, at that same event, Liang Wenbo reached the quarter-finals.

Liang was also runner-up this year in the Shanghai Masters and it is very likely China will have two players in the elite top 16 alongside Hong Kong’s Marco Fu next season.

Ding remains the standard bearer for a nation, even though his form went off the boil after he added the 2005 UK Championship and 2006 Northern Ireland Trophy to his ranking tournament tally.

Efforts to take the World Championship to the Far East were repelled in this decade.

But if China continues to make inroads into snooker, it may be harder to avoid in the next one.

MURPHY'S LAW

htttp://snookerscene.blogspot.com

Shaun Murphy’s capture of the 2005 World Championship came out of the blue.

Murphy had been earmarked as ‘one to watch’ for a number of years, which is usually a poisoned chalice because if results don’t come quickly it gives people the chance to say ‘he’s not as good as they say.’

Well, Murphy proved he was as good as had been suggested.

He had to qualify for the Crucible in 2005. Indeed, he nearly missed out, scraping past Joe Swail 10-8 to reach Sheffield for a third time.

On his first appearance three years earlier he had drawn Stephen Hendry. After losing, he came into the small press conference room to face the assembled media. This can be a forbidding experience for even hardened competitors let alone rookies.

But Murphy took it all in his stride. His self confidence has never been lacking and he spoke of how he wanted to be remembered in the same breath as Hendry and Steve Davis.

A year later, Ken Doherty beat him 10-9 on the black. In 2004, Murphy reached the British Open semi-finals but this hardly pointed to his extraordinary success at the Crucible a few months later.

In the first round he drew Chris Small, by then seriously afflicted by a disease of the spine. Murphy came through before knocking out John Higgins in the second round and thus proving he could handle the game’s big names on its biggest stage.

Davis fell in the quarter-finals and Peter Ebdon provided a stern test in the semis but Murphy won all five frames of the final session to beat him 17-12.

Matthew Stevens held the clear advantage after day one of the final but Murphy, whose rock solid technique is allied to a similarly fierce temperament, never gave up and won 12 of the final day’s 18 frames to win 18-16 and, at just 22, achieve a lifetime’s ambition.

Murphy became the first qualifier since Terry Griffiths in 1979 to win the world title.

His was the last victory under Embassy’s sponsorship and seemed to indicate the end of one era and the start of another.

It hasn’t quite turned out that way but Murphy, firmly ensconced in the world’s top four, is well placed at the age of 27 to achieve plenty more success in the years to come.

He added the UK Championship trophy to his haul of silverware last season and has also won two Malta Cups.

He was in the world final against last season and I would personally be surprised if he didn’t win it again.

DAVIS AND WHITE STILL GOING STRONG

http://snookerscene.blogspot.com

When the 1980s began, Steve Davis and Jimmy White were young men with the world at their feet.

At the start of the 1990s, they were top players and leading title contenders.

As the 2000s dawned, both Davis and White were staring decline in the face but, like the great champions they are, enjoyed memorable resurgences during the decade.

Davis dropped out of the elite top 16 in 2000 after 20 years as part of the elite group. People told him he should retire but his love for the game is such that that was never a possibility.

Instead, he rolled up his sleeves and headed for the qualifiers with mixed results.

Davis, by now part of the BBC television presentation team, missed out on the Crucible in 2001 and 2002 and must have wondered if he would ever return but he did so in 2003 and also earned promotion back to the top 16.

In 2004, he led Ronnie O’Sullivan 8-5 in the Welsh Open final but was edged out 9-8.

The following year he enjoyed an emotional run to the final of the UK Championship, which had been the first title he won as a professional some 25 years earlier.

This was Davis as good as he had ever been. He beat Mark Allen, Stephen Maguire – helped by a 145 total clearance, Ken Doherty and Stephen Hendry to reach his 100th career final.

There, he played the 18 year-old Ding Junhui, 30 years his junior.

There was to be no fairytale ending. Ding won 10-6 but Davis nevertheless authored one of the decade’s most heart warming stories.

White had done similar the previous year when he won his tenth career ranking title and his first in 12 years.

He beat Paul Hunter 9-7 in the Players Championship final in Glasgow and was joined in the arena by his most loyal supporter, his octogenarian father, Tommy, whose good humour and cheerfulness throughout all the setbacks he had endured watching his son had endeared him to everyone in the game.

White had already figured in two other finals, the 2000 British Open and 2004 European Open. His form came and went and his ranking yo-yoed.

In 2006, he was the world no.8 but a disastrous set of results cost him his top 32 place and he ends the decade in danger of dropping off the circuit.

They remain distinctly different characters. Earlier this month Davis played an exhibition at Buckingham Palace; White is currently undergoing hardship in the name of entertainment in the jungle on ‘I’m A Celebrity, Get Me Out Of Here.’

These two legendary players have gone from young pretenders to the game’s elder statesmen.

Davis is now 52, White 47. Neither has anything left to prove but each loves snooker and will stick around for as long as is humanly possible.

Let’s hope it’s a while longer yet.

THE GOLDEN BOY

http://snookerscene.blogspot.com

Paul Hunter’s death in October 2006 was the saddest day of the decade for the snooker world.

He arrived at the Irish Masters 18 months earlier complaining of stomach pains. Everyone assumed this was some passing bug and that we’d hear no more about it, but by the time of the China Open the following month he had already been told he had cancer.

It was a rare form of the disease, at first kept at bay by treatment but which would become terminal.

Bravely, Hunter played on. To see him at tournaments ravaged by chemotherapy, unable to properly feel his hands and obviously not fit to perform at his best was heartbreaking.

Yet he never complained. He never asked ‘why me?’ He didn’t change despite his terrible ordeal.

At the turn of the decade, he was at something of a career crossroads, despite being in his early 20s.

His victory in the 1998 Welsh Open and the financial rewards that went with his early career success led him into spending more time partying than practising.

By his own admission he needed to concentrate more on snooker and, in 2000, he joined forces with Brandon Parker, his manager for the rest of his career.

In 2000, Hunter watched his friend, Matthew Stevens, win the Masters. The following year, he completed the first of three remarkable victories in the game’s leading invitation event.

He trailed Fergal O’Brien 6-2 at the mid session interval and went back to his hotel with Lyndsey, who would become his wife, where they did what couples do.

Two frames into the final session, O’Brien led 7-3 but Hunter then found his range and stormed back to win 10-9.

With his boyish charm in full evidence he later told the press he and Lyndsey had “put plan B into operation.” This was an entirely innocent, off the cuff remark but it would end up as a front page tabloid story and follow him round for the rest of his life. It seemed to mould Paul as ‘one of the boys,’ which indeed he was.

The following year, he fell 5-0 adrift to Mark Williams at Wembley but came back again to win 10-9.

In 2004, he completed the hat-trick, recovering from 7-2 down to beat Ronnie O’Sullivan 10-9.

Hunter’s popularity increased with each of these victories. Television viewers warmed to his natural charm just as they had to that of Jimmy White two decades earlier.

Like White, Hunter was easy to relate to and easy to support.

He could have been world champion but for his illness. He came close in 2003 but let slip a 15-9 lead over Ken Doherty in the semi-finals, the Irishman winning 17-16.

The three Masters victories will, rightly, be what he is remembered for on the table, but he also won two ranking titles during the decade: the 2002 Welsh and British Opens.

Hunter was always good value for the press, be it because of his haircut or his wife or something other than the slog of who beat who in whatever tournament was on that week.

Much of his appeal was that he was always himself: a lad from Leeds who loved snooker and loved life.

The media loved Paul, so too did his fellow players and the public.

He was the golden boy cruelly denied his golden future.

THE BEST FINALS

http://snookerscene.blogspot.com

It was a decade which served up some terrific matches, full of skill and drama that proved whatever problems there may have been off the table, the product on the table has never been better.

Many matches stand out, too many, in fact, to mention here. For that reason, I am limiting this review to finals only.

Hand on heart, I would say the best final of the decade was between John Higgins and Ronnie O’Sullivan at the 2006 Wembley Masters.

This was two of the greatest players of all time on top of their games going toe-to-toe right to the final ball.

When O’Sullivan missed match ball red to a middle pocket by a couple of millimetres in the decider, Higgins produced the best clearance of his career, 64, to land the title.

It was a fitting way for the Wembley Conference Centre’s last ever match to end.

Deciding frame finishes of course always throw up plenty of excitement, especially in finals.

O’Sullivan had three years earlier beaten Higgins 10-9 to win the Irish Masters. I remember in the decider he refused to roll up behind the brown after potting a red and instead blasted it into the middle before going on to win match and tournament.

This was part of a golden run of finals in 2003 that began when O’Sullivan beat Stephen Hendry 9-6 to win the European Open in a final that nobody saw because the tournament wasn’t televised.

I saw it and the standard was superb, although not as high as their British Open final a few months later, which included five successive centuries. Hendry won 9-6 in what was arguably his finest performance of the decade.

And the Crucible final that year saw Mark Williams hold off Ken Doherty, who recovered from 11-4 down to 12-12 before losing 18-16.

Williams’s first world title triumph in 2000 had seen him come from 13-7 down to edge Matthew Stevens 18-16.

Peter Ebdon felt the pressure at 17-16 up on Hendry in the 2002 final but admirably held himself together to win the decider.

And Higgins’s 2007 victory over Mark Selby was dramatic because of the way Selby came back at him, from 12-4 down to trail just 14-13 before the Scot stepped it up to win 18-13.

The previous year, Graeme Dott and Ebdon fought out a long but fascinating battle which Dott won 18-14.

The last ever Embassy sponsored world final saw Shaun Murphy outlast Stevens 18-16 in what was a gripping battle.

Murphy would lose 10-9 to Stephen Maguire in the 2008 China Open final, a match which kept a nation riveted until gone midnight.

At the Masters, Paul Hunter won three 10-9 deciders in four years, victories which hugely boosted snooker’s profile and proved its ability to produce exciting matches featuring dynamic characters the public could easily identify with.

The first Masters final of the decade brought heartbreak for Doherty, who missed the black off its spot for what would have been a 147 against Stevens, who compounded the misery by beating him 10-8.

Indeed, Doherty endured his fair share of disappointment in finals, also losing 10-9 to Williams in the 2002 UK Championship final.

Williams also came from 8-5 down to beat Anthony Hamilton 9-8 and win the 2002 China Open in Shanghai. I will always give Anthony credit for his refusal to make any excuses and blame anything other than his own lack of nerve as the pressure grew.

At the Welsh Open, O’Sullivan came from 8-5 down to beat Steve Davis 9-8 in 2004 and edged Hendry 9-8 after a terrific contest in 2005. Remarkably, this is the last time any player has successfully defended a ranking title.

The 2007 Welsh event saw unlikely finalist Andrew Higginson storm back from 6-2 down to lead Neil Robertson 8-6 before the Aussie fell over the line at 9-8.

In 2008, Mark Selby outdid O’Sullivan sufficiently to come back and beat him 9-8.

Though close finals tend to be regarded highly and remembered fondly, there were a number of superb performances by players winning easily.

O’Sullivan featured in the first of these this decade when he swept aside Ken Doherty 10-1 to win the 2001 UK Championship. Maguire did similar to David Gray in 2004 and O’Sullivan then thrashed Maguire 10-2 in 2007.

The Rocket also powered to a 10-3 victory over Higgins in the 2005 Masters final and beat Ding Junhui by the same score in 2007.

Ding, treated to great hostility by sections of the Wembley crowd and completely outplayed, tried to concede at 9-3.

For me, though, the best single performance has to be Higgins’s remarkable four successive centuries and 494 unanswered points against O’Sullivan in the 2005 Grand Prix final because it was a spell of utterly unstoppable snooker.

The 2000s was a decade in which standards across the board improved and the titles were more shared around than ever before.

And, my word, some of the snooker was sensational.

WILLIAMS MAKES HIS MARK

htttp://snookerscene.blogspot.com

Mark Williams may have gone off the boil in the latter part of the decade but, in its early years, he was the game’s most consistent force.

Ronnie O’Sullivan said, after beating him to reach the 2001 UK Championship final, that he would happily pay for him to go and lie on a beach so that he wouldn’t have to play him again.

With Williams at his best, it wasn’t just about potting and breakbuilding. He had a guile and table-craft that undid many a player.

When he won the 2003 LG Cup it meant he simultaneously held all four BBC titles, something only Steve Davis and Stephen Hendry had previously accomplished.

And when Williams was world no.1 he was as authentic a top dog as those twin titans.

A fiercely talented long potter, Williams was a better player than had been widely recognised. One of his great skills was in finding ways to win matches when not at his best. He invariably scrapped through a couple of rounds before upping his game and peaking at the business end of tournaments.

He trailed his fellow Welshman, Matthew Stevens, 13-7 in the 2000 World Championship final but, with his iron will to win kicking in, recovered to beat him 18-16.

It didn’t go to his head. His laid back nature – a stark contrast to his competitive disposition in the arena – remained despite his success.

He was in some ways a reluctant world no.1. Media interviews did not come easily to him. He didn’t push himself forward or attempt to cultivate an image for himself.

On the table, he was on fire. From February 1998 to November 2003 he successfully negotiated the opening round of 48 successive ranking events, a record that will take some beating.

In this period he won a second UK Championship title, pipping Ken Doherty 10-9 in 2002.

Doherty was also his victim in a thrilling 2003 Crucible final, which Williams led 11-4 before being severely tested and eventually winning 18-16.

He also won a second Wembley Masters title in 2003 and that year became only the third player, after Davis and Hendry, to win the ‘big three’ in the same season.

He thus became – and remains – only the second player to win more than £700,000 in a single campaign.

In 2005, he made a Crucible maximum but Williams’s consistency left him for various reasons, one of which was possibly a sense of contentment at his achievements.

He won the 2006 China Open but would drop out of the top 16 in 2008 after some very disappointing results.

He’s back now and, though not fully returned to his best, is still a player nobody wants to draw.

THE LION IN WINTER

http://snookerscene.blogspot.com

Stephen Hendry began the decade as world champion and ends it as world no.10.

This represents a decline but it has not been a dramatic one, more a gradual falling away and, make no mistake, he’s still a tough proposition and as determined as ever.

Hendry won four ranking titles during the decade, the last in 2005. He appeared in 12 ranking finals. Only Ronnie O’Sullivan, John Higgins and Mark Williams featured in more.

But his chief battle was with his own past. This was a man who won 27 titles and appeared in 38 finals from the 90 ranking events staged in the 1990s.

At one stage he won five in a row. The last time someone won two in a row in this decade was five years ago.

Such an unprecedented record of success could never be sustained and so any dip in form would be pounced on by those wishing to say he was no longer the force he once was.

And, of course, he isn’t but, as he proved at the Crucible just this year, he is capable of raising his game on the big occasions, though not for prolonged enough spells to seriously threaten for major titles.

Let us also remember that his consistency enabled him to return to the top of the rankings in 2006.

For fans of the 90s Hendry, it can be painful watching him struggle. Yet, when commentators say things such as “he never missed a long ball 15 years ago” they are quite obviously wrong. He, like all players, had his off days, even in his pomp. He just has more now than he did then.

And the difference now is that attention is more acutely focused on his mistakes because they appear to represent a general narrative: that this is a legend in sad decline, never to recapture former glories.

Stephen himself has spoken of the “chaos in my head” when he’s at the table. This stems from his own inability to accept that he isn’t the Hendry of old. He is perhaps expecting too much of himself. When, as Steve Davis did, he comes to terms with the fact that the golden age has gone, he may relax a little more and find some form.

To still be good enough to occupy tenth place in the rankings at the age of 40 proves how good he can still be.

For hour upon hour in his snooker room at home, he puts in the work. Just as in all those finals against Jimmy White, the desire to prove people wrong, to prove himself, still burns deep.

He no longer dominates the game but, rest assured, Hendry will forever, in the words of Dylan Thomas, rage against the dying of the light.

KING JOHN'S REIGN

http://snookerscene.blogspot.com

When John Higgins won his first world title in 1998, I assumed he would go on to win four or five.

As it transpires he still might, but this looked unlikely at the mid point of the decade when it appeared as if Higgins had gone off the boil.

He began the 2000s as world no.1 and indeed won its first ranking title, the Welsh Open.

He picked up a second UK title in 2000 and the following year won the first three tournaments of the 2001/02 season.

During the last of these he became a father for the first time. There’s no doubt this had a bearing on his career. Higgins is from a close family and he found himself enjoying home life more than the relentless hours in the club.

He thus went three years between ranking titles before his success in the 2004 British Open and dropped to sixth in the rankings, too low for a player of his ability.

Things changed, though, as the decade wore on. For a variety of reasons he rediscovered his competitive spirit.

In 2005, he compiled four successive centuries and amassed 494 points without reply in destroying Ronnie O’Sullivan 9-2 to win the Grand Prix.

He made a tremendous under pressure 64 clearance to pip O’Sullivan to the 2006 Masters title.

But he had been putting himself under it too much to win the world title again.

His fortunes seemed to turn round after Mark Williams beat him 17-15 from 14-10 down in their 2000 semi-final, a defeat Higgins attributes in large degree to Williams forgetting to shake his hand before their final session.

For five successive years Higgins failed to get past the quarter-finals at Sheffield but in 2007, despite not being in prime form ahead of the 17 day marathon, he went all the way to the title.

Then last season he won a third and demonstrated, in particular against Jamie Cope and Mark Selby, his ability to produce his best snooker while under pressure.

Virtually every professional regards Higgins as the best all round player in the game but also look up to him as a person.

He exudes a friendly, down to earth air despite his success. His fellow players like him and they respect him.

This means he is influential in off table matters, which he has taken a leading role in through the formation of the World Series and the new Snooker Players Association.

Having started the decade as a staunch WPBSA supporter, Higgins ends it as one of the most vocal critics of the governing body.

But it is as a player that he remains prominent. He will most likely end the decade as provisional world no.1 having started it as official no.1.

Despite a few slip ups during the last ten years, this is proof of Higgins’s undoubted class.

PLAYER OF THE DECADE

http://snookerscene.blogspot.com

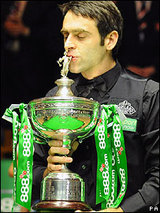

Ronnie O’Sullivan was the player of the decade, in terms both of most titles won and in the way in which he bestrode the sport as its biggest draw and brightest star.

The 2000s began with O’Sullivan in some personal distress. He checked himself into the Priory Clinic to receive treatment for addiction and depression but despite some well publicised blow ups, kept himself on an even enough keel to realise his full potential as the decade wore on.

On the final night of the 2001 World Championship, O’Sullivan watched as former winners of the title took part in a ‘Champions Parade.’

Ridiculously, Jimmy White was invited to take part, despite the fact he had never won the title.

O’Sullivan looked on as his friend, six times the Crucible runner-up, took his applause and resolved never to put himself in the same position.

He would beat John Higgins in arguably the highest quality of all 10 world finals staged during the decade. Theirs was a rivalry born out of friendship and mutual respect. At the end of the final, Higgins told him he was happy for O’Sullivan’s father that he had won the title, a gesture much appreciated by Ronnie junior.

More titles came: a total of three world crowns, two more UK trophies to add to the two he had won in the 1990s and three more Masters victories in addition to his 1995 success.

But there were slumps as well, including a two and half year gap between winning ranking titles at the 2005 Irish Masters and 2007 UK Championship.

O’Sullivan took instantly to the Premier League’s shot-clock and, with one to go, has hoovered up every title under the format – five in a row, taking his total haul from the decade to seven.

He achieved a level of consistency hitherto lacking in his career and spent a total of five years as world no.1.

There were, of course, headlines for other reasons, ranging from the explosive to the bizarre.

O’Sullivan was extremely unwise to bad mouth Stephen Hendry in such graceless terms before their 2002 Crucible semi-final, which Hendry devoted every conceivable ounce of energy and concentration into winning.

In 2006, he walked out of his match against Hendry at the UK Championship, a gross lapse in professionalism to some, proof of the debilitating effects of his depression to others.

In China in 2008 his crude behaviour in a press conference was front page news, although it soon began to look like a lot of fuss about very little.

The cracks in his fragile character were laid bare at the Crucible in 2005 when he went to pieces as Peter Ebdon grimly ground him down in their World Championship quarter-final.

Yet it is these very human qualities that have endeared O’Sullivan to so many. And it is he, more than any other player, who has drawn new fans to the sport, particularly in areas such as Europe and China where snooker has grown in considerable ways in the last ten years.

O’Sullivan cannot boast the consistent record Hendry enjoyed in the 90s but has been responsible for many of the most memorable moments of this decade.

In 2007, he made a century in each of the five frames he won against Ali Carter in the Northern Ireland Trophy.

The same year he ended an epic UK Championship semi-final against Mark Selby with a maximum.

He lost two terrific Masters finals in deciders, first to Paul Hunter in 2004 and then to Higgins in 2006.

And he destroyed Higgins in the 2005 Wembley final and then Ding Junhui in 2007, putting together snooker Steve Davis described as “unplayable.”

For O’Sullivan, this was a decade in which, for all his frailties and love-hate relationship with snooker, he came of age as a player.

Our sport should consider itself lucky to have him.

INTRODUCTION

http://snookerscene.blogspot.com

I shall, in the coming weeks on this blog, be looking back at the last ten years in snooker as the decade comes to an end.

It was a decade that began with snooker still in fine fettle. There was an undisputed ‘big four’ of John Higgins, Stephen Hendry, Mark Williams and Ronnie O’Sullivan and the circuit was awash with tournaments, both ranking and invitational, both in the UK and beyond.

But the warning signs were there too. The election of the Labour government in 1997 meant the end of tobacco sponsorship in 2003, with the World Championship exempt until 2005.

As it transpired, there were 77 ranking events staged during the decade compared with 90 in the 1990s.

Here’s who won the most:

Ronnie O’Sullivan – 15

Mark Williams – 9

John Higgins – 8

Peter Ebdon – 6

Stephen Hendry, Ken Doherty, Stephen Maguire, Neil Robertson – 4

Shaun Murphy, Ding Junhui, Stephen Lee – 3

And here’s who appeared in most ranking tournament finals:

Ronnie O’Sullivan – 22

Mark Williams, John Higgins – 14

Stephen Hendry – 12

Ken Doherty – 9

Peter Ebdon – 8

Shaun Murphy, Stephen Maguire – 6

Stephen Lee, Graeme Dott – 5

All of the above figures of course exclude next month’s UK Championship.

They provide a snapshot of who has performed best in the biggest events, although don’t include the premier invitation tournaments.

Of these, O’Sullivan and Paul Hunter each won the Masters three times, O’Sullivan and Higgins won two Scottish Masters titles apiece, Higgins captured two Irish Masters crowns and O’Sullivan was victorious in a remarkable seven stagings of the Premier League.

There were 35 maximums recorded in competitive play, nine more than in the 1990s. O’Sullivan was responsible for six of them and Higgins five.

In 2004, Jamie Burnett compiled the first break of more than 147 with his 148 in the UK Championship qualifiers.

In 2003, Mark Williams picked up the biggest ever first prize when he landed a cheque for £270,000 for winning the World Championship but overall prize money is lower than it was at the turn of the decade.

Only six players who were in the elite top 16 when the 2000s began are still there.

Higgins was first and is now fourth, Stephen Hendry was second and is now tenth, Williams was third and is now 15th and O’Sullivan was fourth and is now first.

Peter Ebdon was 13th and is now 14th; Mark King was 14th and is now 16th.

In the case of Williams and King, they each dropped out of the top 16 before returning.

O’Sullivan was world no.1 for a total of five years, Williams for three, Higgins for two and Hendry for one.

The biggest single viewing audience in the UK was the 7.8m who tuned in for the climax of Ebdon’s 2002 Crucible victory over Hendry but this is dwarfed by viewing figures recorded in China.

We lost many well known faces. Hunter succumbed to cancer at just 27 while stars of an earlier era – John Spencer, Eddie Charlton and Bill Werbeniuk – also died.

David Vine, a face synonymous with TV snooker for a generation of fans, passed away as did other members of snooker’s supporting cast, including referees John Smyth, John Street and Colin Brinded, Imperial Tobacco supremo Peter Dyke and TV commentator Jack Karnehm.

Snooker became big in China following Ding Junhui’s extraordinary capture of the 2005 China Open title in Beijing.

In its traditional base in the UK there was a downturn in interest as snooker clubs – including many that had been home to young kids who went on to become big stars – closed down in large numbers.

Snooker’s media profile decreased in Britain but grew elsewhere, particularly in Europe following a landmark broadcast deal with Eurosport.

There was the usual political wrangling as the players rejected first a breakaway circuit and then a serious investment offer.

Snooker started to embrace the internet as a tool for growth and provided many memorable television moments.

New faces appeared, old faces disappeared, the snooker world continued to turn and, through it all, the game remains intact.

Over the next few weeks I will be examining the players, the matches and the controversies that have marked out the last ten years on the green baize.

29. 4. Robert

Návštěvnost stránek

ANTEE s.r.o. - Tvorba webových stránek, Redakční systém IPO

![ding double[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1630488&width=227&height=300)

![murphy world[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1603100&width=260&height=226)

![hunter masters[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1594456&width=260&height=217)

![ronnie john[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1591532&width=203&height=152)

![williams_trophy[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1590652&width=245&height=245)

![hendry wave[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1590066&width=260&height=309)

![higgins casual[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1587676&width=250&height=299)

![ronnie_white[1].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1586182&width=260&height=372)

![Welsh Open[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=3689245&width=160&height=174)

![Ronnie_OSullivan_Snooker_Champion_PTC7_2011[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=2439625&width=160&height=151)

![topimage[2].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=2498497&width=160&height=141)

![08%20pls%20ronnie%20trophy[3].jpg](image.php?nid=1380&oid=1189442&width=160&height=198)